The spin of the electron is

nature's perfect quantum bit, capable of extending the range of information

storage beyond "one" or "zero." Exploiting the electron's

spin degree of freedom (possible spin states) is a central goal of quantum

information science.

Recent progress by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) researchers Joseph Orenstein, Yue Sun, Jie Yao, and Fanghao Meng has shown the potential of magnon wave packets—collective excitations of electron spin—to transport quantum information over substantial distances in a class of materials known as antiferromagnets.

Their work upends conventional understanding about how such excitations propagate in antiferromagnets. The coming age of quantum technologies—computers, sensors, and other devices—depends on transmitting quantum information with fidelity over distance.

With their discovery, reported in a paper published in Nature Physics, Orenstein and coworkers hope to have moved a step closer to these goals. Their research is part of broader efforts at Berkeley Lab to advance quantum information by working across the quantum research ecosystem, from theory to application, to fabricate and test quantum-based devices and develop software and algorithms.

Electron spins are responsible for magnetism in materials and can be thought of as tiny bar magnets. When neighboring spins are oriented in alternating directions, the result is antiferromagnetic order, and the arrangement produces no net magnetization.

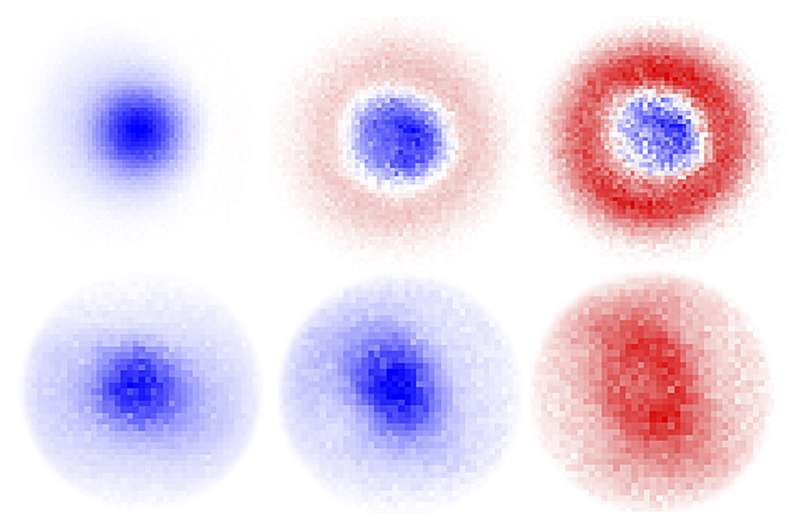

To understand how magnon wave packets move through an antiferromagnetic material, Orenstein's group used pairs of laser pulses to perturb the antiferromagnetic order in one place while probing at another place, yielding snapshots of their propagation. These images revealed that magnon wave packets propagate in all directions, like ripples on a pond from a dropped pebble.

The Berkeley Lab team also showed that magnon wave packets in the antiferromagnet CrSBr (chromium sulfide bromide) propagate faster and over longer distances than the existing models would predict. The models assume that each electron spin couples only to its neighbors. An analogy is a system of spheres connected to near neighbors by springs; displacing one sphere from its preferred position produces a wave of displacement that spreads with time.

Surprisingly, such interactions predict a speed of propagation that is orders of magnitude slower than the team actually observed.

"However, recall that each spinning electron is like a tiny bar magnet. If we imagine replacing the spheres with tiny bar magnets representing the spinning electrons, the picture changes completely," Orenstein said. "Now, instead of local interactions, each bar magnet couples to every other one throughout the entire system through the same long-range interaction that pulls a refrigerator magnet to the fridge door."

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top