Created by postdoctoral researcher Egidijus Auksorius and Prof. Claude Boccara, the scanner utilizes a technique known as optical coherence tomography (OCT). This is already used in medical imaging, and involves analyzing the interference pattern that occurs when two beams of light are combined – one of those beams serves as a reference, while the other is shone through a biological sample.

In this way, the scanner can image the "internal fingerprint" located about half a millimeter below the surface of the skin, which has a pattern identical to that on the outside – except it’s unscathed.

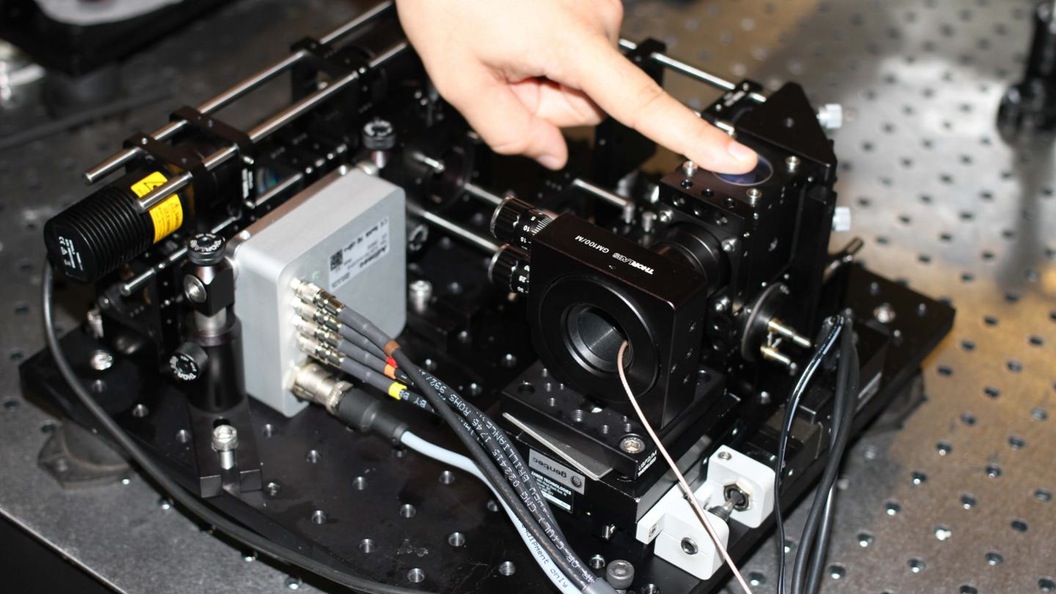

While existing OCT machines are relatively big and expensive, the scientists are using a more compact version of the technology called full-field OCT (FF-OCT). As a result, their scanner is currently about the size of a shoebox, although they’re working on making it smaller, faster-operating and able to scan deeper. Its most expensive component is a US$40,000 specialized infrared camera, although they’ve recently had success using a camera worth about one-fifth as much.

Ultimately, they hope to produce a finished product that could be made for just under $10,000. This means that it won’t likely be finding its way into consumer products anytime soon, but would instead be utilized in settings where security is particularly important. That said, scientists at the University of California, Davis and Berkeley are working on an ultrasound-based 3D fingerprint reader that could replace capacitive scanners on mobile devices.

Plans call for the Langevin device to be field-tested on 100 individuals, in Turkey. A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Biomedical Optics Express.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top