It will be a while until Vietnamese ports could stand with others in the region. Until then, Vietnam’s government and local authorities will have to rely on many other incentives to attract foreign investors and global traders. Below are some key seaports and their development projects until 2010.

It will be a while until Vietnamese ports could stand with others in the region. Until then, Vietnam’s government and local authorities will have to rely on many other incentives to attract foreign investors and global traders. Below are some key seaports and their development projects until 2010.

(Pictures) Danang Port, Vietnam

Vietnam’s impressive and consistent growth over the last several years (second in Asia to China) has made Vietnam more and more visible on the global map, especially for those multinational corporations looking for an outsourcing and factory-relocating destination. Vietnam has achieved this success through hard work and the willingness of the government to respond to investor concerns. However, there exists a hindrance that is not discussed much in the daily news yet has hampered both foreign investors and Vietnamese companies with international market ambition: the ports.

To compete for foreign investment with other developing countries, Vietnam has relied most on the strength of its’ abundant and low cost labor force, a highly educated young generations, inexpensive operation costs, and many other incentives signaling the government’s warm welcome to investors and its determination to integrate into the global market. Vietnam’s rapid economic development, however, was not matched by rapid development in infrastructure. As a result, Vietnam ports and roads remain underdeveloped compared to those of other countries in the region, such as China and Thailand, which in turn has become an impediment to those who wish to expand their business to Vietnam. We make this point not to frighten investors as we still believe Vietnam makes a lot of sense as a place to locate an Asian factory or open a buying office. It is, however, a reality that investors need to consider and plan for.

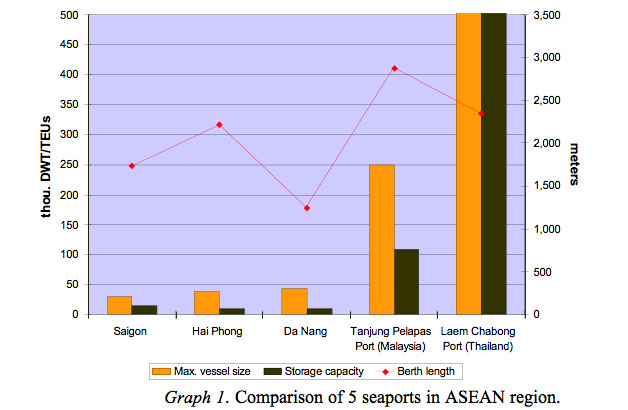

Along her 3,200km-long coastline, Vietnam has a total of 114 seaports, 14 of which are relatively large and named as the keys to economic development. However, most ports are relatively small with obsolete facilities and poor supporting services. Take the three largest ports of Vietnam – Saigon port (south), Hai Phong port (north), and Da Nang port (central) – and compare them to some major seaports of Thailand and Malaysia (see graph 1 below). When juxtaposed with them, the three main ports of Vietnam seem diminutive in terms of maximum vessel size allowed and storage capacity in despite the roughly similar size of berth lengths (the figures are for container terminals only; for Thailand, it is 1.2m DWT for maximum vessel size and 4m TEUs storage capacity).

The limited size of Vietnamese ports entails transportation of goods from Vietnam to major international market such as USA and the European Union to be transshipped at larger ports, including Hong Kong and Singapore. Transshipment means additional handling of shipments, which is more expensive. Consequently, the added shipping cost drives up the product costs and can help to decrease Vietnam’s definite advantage vis-à-vis China and Thailand in lower labor cost that Vietnam takes pride on. A comparison of shipping costs for the same item from various seaports to Los Angeles, USA shows that shipping from Vietnam shows a significantly higher fee. A 40-foot container of the same item shipped from Hong Kong is 28% more than from Ho Chi Minh City. From Shanghai, Ningbo or Shenzhen the rate is not as high, only 16% more expensive but still highly significant in the context of an export intensive. Factoring in the delay in transaction due to transshipment, and one can see why foreign investors are having to look long and hard at their Vietnam costs even though labor savings can me substantial: the true export price is greatly influenced by the higher shipping costs.

|

Saigon Port, more than 130 years old, has had the highest throughput and productivity per annum of the country for years. Situated on what was the outskirts but is now the outskirts or suburbs of Ho Chi Minh City, it has however shown some drawbacks, casting much concern for the government. Being in the middle of the busiest city of the nation means ground transportation to and from the port has to deal with traffic congestion similar to other big Asian cities, and expansion of the port is not an option regardless of the high throughput. Meanwhile, Saigon port assumes the role of the major port in the south, where cargos and containers come and go from all industrial parks in the southern region. |

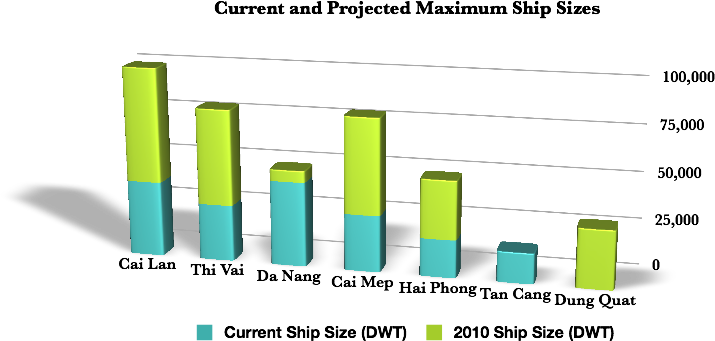

In August 2006, the authorities officially announced that Saigon Port would be relocated to Cat Lai and Hiep Phuoc; the new plan not only resolves the limited size, obsolete facilities and traffic issues, but also becomes more efficient as the new port complex is located conveniently among the region’s industrial parks and export processing zones of Ho Chi Minh City, Binh Duong, Dong Nai, and Ba Ria – Vung Tau. When finished, the new ports will resume Saigon Port’s role in international and domestic trade. The new deep-sea port in Hiep Phuoc is designed to cater vessels of up to 50,000 DWT (dead weight ton). In 2005, Cat Lai port also went through an expansion in which it was equipped with more modern equipment. Furthermore, Saigon Port is seeking the government’s approval to develop Cai Mep port complex and Thi Vai International General Port. If approved, these are slated to be completed in 2010, and will be able to receive vessels of up to 80,000 DWT.

In 1999, the Prime Minister of Vietnam signed a decision approving implementation of a master plan for the development of Vietnam’s seaport system until 2010. A revaluation after 6 years nonetheless has revealed many frustrations and criticism from analysts and concerned parties. For instance, Hai Phong complex port could allegedly handle vessels up to 40,000 DWT, but only ships below 10,000 tons can gain access to the port at present. Others have to dock at distant transshipment points. This common problem arises at Dinh Vu (Hai Phong) and Cai Lan (Quang Ninh) ports as well.

But that is not all. Many display doubt towards the plan’s completion by 2010. While construction has been started on Cai Mep Container Port, Cai Mep-Thi Vai International Port has yet to engage a technical consultant for the project. The skepticism is further spread as concerns regarding the site’s geological structure have emerged and been reported in the press. Now the Ministry of Communications and Transport plans to hire a consultant to further study and recommend a solution of the issue, revision of investment cost is virtually inevitable, and hence, the plan is most likely to fall further behind schedule.

Similar to many investment projects in Vietnam, seaport projects face a common problem of local authorities fighting for State funds and attention. Thus, the State funds cake is cut into small pieces, resulting in scattering and undersized ports in several provinces. Yet, Vietnam still lacks an international-standard port with large capacities that could enhance the country’s rising exports and economy.

Apart from the inadequate infrastructure, Vietnam ports are facing another setback due to backward pricing. Responding to a question during the Vietnam Port Association’s Conference in August 2006, Mr. Cao Tien Thu – director of Hai Phong port – commented on this matter and urged the government to issue a pricing scheme to cope with existing problems. “While most seaports in other countries only charge port dues depending on the vessels’ GRT (gross registered tons),” Mr. Thu said, “Vietnamese ports are requiring seven different types of fees, some of which are trifling. We should incorporate several of them together and make it more manageable.” The rapid increase in number of ports also created a “race to the bottom” situation, where Vietnam ports have reduced their price to attract customers. The direct results are lower service quality and an inability to reinvest into port development. Mr. Thu’s suggestion is a one-price scheme based on the price of other ports in the region with an adjustment band of 10-15%.

Nevertheless, the Vietnamese government deserves some credits towards their acknowledgement of the seaports’ importance. More and more ports are being renovated and updated to meet international standards; plans are being materialized, not just on paper. In July 15, 2006, the construction of the largest new port in central Vietnam – Dung Quat – commenced. It is designed to accommodate ships of up to 30,000 DWT. The port will help many surrounding industrial parks as well as the central region’s economy in general. Along with the new Saigon port complex, Dung Quat port is slated to handle some of the heavy traffic of the current Saigon port. In the north, a port complex – a major expansion of Quang Ninh port – is also being shaped. If approved, the new port will be able to host 100,000 DWT vessels with four-times larger capacity than Hai Phong port. All of these actions and the expansion of the ports around Ho Chi Minh City are helping to improve shipping availability and will ultimately improve shipping prices.

It will be a while until Vietnamese ports could stand with others in the region. Until then, Vietnam’s government and local authorities will have to rely on many other incentives to attract foreign investors and global traders. Below are some key seaports and their development projects until 2010.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top