|

Custom-made "biosynthetic" corneas can restore vision in

humans as well as donor corneas a new study reveals. Corneas made in the laboratory have markedly improved the sight of 10 Swedish patients with significant vision loss. |

|

Custom-made "biosynthetic" corneas can restore vision in humans as well as donor corneas a new study reveals. Produced entirely from synthetic collagen, the implants offer the tantalising possibility for a replacement to human donor tissues. The custom-made corneas work by prompting regeneration of the nerves and cells in the eye. This is the first time vision has been restored in this way. Our ability to see depends on the cornea, the transparent layer that covers the pupil, iris and front of the eye. Made entirely of collagen, it refracts light to focus images on the retina. |

|

|

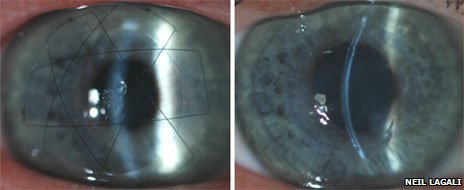

Damage to the cornea is the second biggest cause of blindness worldwide, affecting nearly 10 million people. In countries where tissue banking is possible, corneal damage and disease is treated by implanting human donor corneas. But there is a worldwide shortage. The "biosynthetic" implants were made from a synthetic version of human collagen designed to mimic the cornea as closely as possible. Fibrogen, the company that made the implants used yeast and human DNA sequences to create the custom corneas. Diseased tissue was removed from the corneas of 10 patients and replaced with the implants. They were then followed for two years after surgery to monitor how well the implants were incorporated into the eye. In six of the patients, vision improved from about 20/400 to 20/100 which means they could see objects four times further away than before the operation. Sight was restored in all 10 patients who received the artificial implants. However, a number of the patients needed additional assistance from contact lenses. They were all on the waiting list in "Our goal was actually just to test the safety of these corneas in humans so the improvement in vision was a real bonus for us." 'Recreate a cornea' The success of the implants is down to their ability to allow tissues in the eye to regrow. "The patients' own cells and nerves that grow back into this prefabricated scaffold recreate a cornea which resembles normal healthy eye tissue. So essentially it's stimulating regeneration."

(L) Biosynthetic cornea 24 hours after surgery showing the sutures holding the cornea in place.

"Nerve regeneration was faster in all patients than it would have been if they had received a human graft." Professor Griffith told BBC News. The patients did not experience any problems of rejection of the implant and they did not need long term immune suppression. Both are serious side effects associated with the use of human donor corneas. Because the cornea is responsible for controlling light that enters the eye it needs to be transparent so has no blood supply. It gets its oxygen from tear fluid. All the biosynthetic corneas were able to produce normals tears as well as becoming sensitive to touch. Prosthetic corneas made from synthetic plastic are already used for patients who have previously had unsuccessful donor grafts but these can be difficult to implant and can cause infection, glaucoma and detachment of the retina. The authors are keen to stress this is only an initial clinical study on 10 people but are optimistic about its potential once further clinical trials are done. The research is published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. |

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top