Weather data may reveal more about lives of airborne animals

Weather data may reveal more about lives of airborne animals

The blips and blobs caused by flying animals may look like noise to storm-watchers studying Doppler radar data, but these signals could be a big hit with bat biologists.

The blips and blobs caused by flying animals may look like noise to storm-watchers studying Doppler radar data, but these signals could be a big hit with bat biologists.

Bats swirling out of caves show up on weather radar, as do masses of birds and other flying animals. Now that the National Severe Storms Laboratory in

Bats swirling out of caves show up on weather radar, as do masses of birds and other flying animals. Now that the National Severe Storms Laboratory in

Biologically speaking, the air is “a very unexplored part of our biosphere,” said Thomas Kunz of

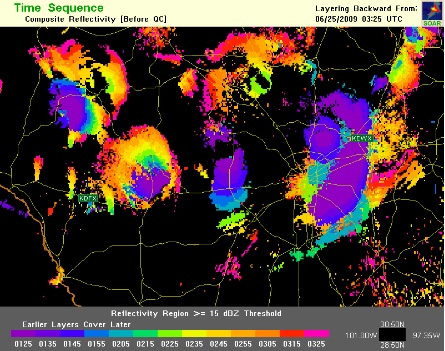

At the meeting, Frick described how, in a radar sequence from southern

In the radar view of a storm front rolling over

Radar monitoring of airborne critters had meeting attendee and environmental educator Susannah Graedel of

Networked radar data also inspired Frick, Kunz and their colleagues to put a weather spin on studies of the tradeoffs bats make in timing their hunts. Two years of radar data showed that after hot days during a drought, bats tended to emerge earlier in the evening. Earlier meant more light in which hawks and other predators could nail a bat. Yet during a dry year, insects are scarcer and bats appear willing to take the risk, showing up early for the evening flights of moths and other insects. Simple thirst may drive bats out of caves earlier too, especially the nursing females. (Baby bats require prolonged nursing “equivalent to if we nursed our young until they’re teenagers,” Frick said.) In a wetter year with presumably better hunting, however, hot days didn’t provoke bats to take such risks.

From a radar perspective, bats are just another kind of cloud. And Frick is now working with meteorological radar physicist Phillip Chilson at the

The radar studies help reveal how, much like sea creatures seek out upwellings of nutrient-rich water or surf along currents, flying animals navigate the changing landscape of their ocean of air. “I had never thought of air as a dynamic habitat before,” Frick said.

In the last several years the storm lab has developed combined data from the nation’s 156 NEXRAD Doppler installations and is working on incorporating radars from major airports. These new radar networks will better enable biologists to take advantage of the method to study living things in the air. “Networks — that’s the exciting and powerful thing,” Chilson said.

Weather radar has limitations, Chilson said. For example, coverage fades as the Earth curves down beneath any radar beam. Yet there’s a lot of data available online (at a cooperative NSSL website), including a raw version of interest to biologists. Not so for weather watchers: The signs of bats and birds amount to, Chilson said, “stuff that meteorologists try with a passion to get rid of.”

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top