An

eminent UK engineer is suggesting building cloud-whitening towers in the Faroe

Islands as a "technical fix" for warming across the Arctic.

Scientists

told UK MPs this week that the possibility of a major methane release triggered

by melting Arctic ice constitutes a "planetary emergency".

The

Arctic could be se a-ice free each September within a few years.

a-ice free each September within a few years.

Wave

energy pioneer Stephen Salter has shown that pumping seawater sprays into the

atmosphere could cool the planet.

The

Edinburgh University academic has previously suggested whitening clouds using

specially-built ships.

At

a meeting in Westminster organised by the Arctic Methane Emergency Group

(Ameg), Prof Salter told MPs that the situation in the Arctic was so serious

that ships might take too long.

"I

don't think there's time to do ships for the Arctic now," he said.

"We'd

need a bit of land, in clean air and the right distance north... where you can

cool water flowing into the Arctic."

Favoured

locations would be the Faroes and islands in the Bering Strait, he said.

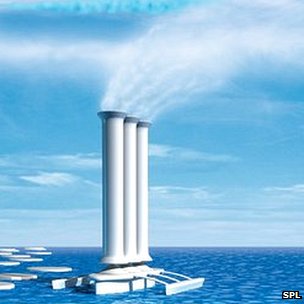

Towers

would be constructed, simplified versions of what has been planned for ships.

In

summer, seawater would be pumped up to the top using some kind of renewable

energy, and out through the nozzles that are now being developed at Edinburgh

University, which achieve incredibly fine droplet size.

In

an idea first proposed by US physicist John Latham, the fine droplets of

seawater provide nuclei around which water vapour can condense.

This

makes the average droplet size in the clouds smaller, meaning they appear

whiter and reflect more of the Sun's incoming energy back into space, cooling

the Earth.

On melting ice

The

area of Arctic Ocean covered by ice each summer has declined significantly over

the last few decades as air and sea temperatures have risen.

For

each of the last four years, the September minimum has seen about two-thirds of

the average cover for the years 1979-2000, which is used a baseline. The extent

covered at other times of the year has also been shrinking.

What

more concerns some scientists is the falling volume of ice.

Peter

Wadhams, professor of ocean physics at Cambridge University, presented an

analysis drawing on data and modelling from the PIOMAS ice volume project at

the University of Washington in Seattle.

It

suggests, he said, that Septembers could be ice-free within just a few years.

“In

2007, the water [off northern Siberia] warmed up to about 5C (41F) in summer,

and this extends down to the sea bed, melting the offshore permafrost."

Among

the issues this raises is whether the ice-free conditions will quicken release

of methane currently trapped in the sea bed, especially in the shallow waters

along the northern coast of Siberia, Canada and Alaska.

Methane

is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, though it does not

last as long in the atmosphere.

Several

teams of scientists trying to measure how much methane is actually being

released have reported seeing vast bubbles coming up through the water -

although analysing how much this matters is complicated by the absence of

similar measurements from previous decades.

Nevertheless,

Prof Wadhams told MPs, the release could be expected to get stronger over time.

"With

'business-as-usual' greenhouse gas emissions, we might have warming of 9-10C in

the Arctic.

"That

will cement in place the ice-free nature of the Arctic Ocean - it will release

methane from offshore, and a lot of the methane on land as well."

This

would - in turn - exacerbate warming, across the Arctic and the rest of the

world.

Abrupt

methane releases from frozen regions may have played a major role in two

events, 55 and 251 million years ago, that extinguished much of the life then

on Earth.

Meteorologist

Lord (Julian) Hunt, who chaired the meeting of the All Party Parliamentary

Group on Climate Change, clarified that an abrupt methane release from the

current warming was not inevitable, describing that as "an issue for

scientific debate".

But

he also said that some in the scientific community had been reluctant to

discuss the possibility.

"There

is quite a lot of suppression and non-discussion of issues that are difficult,

and one of those is in fact methane," he said, recalling a reluctance on

the part of at least one senior scientists involved in the Arctic Climate

Impact Assessment to discuss the impact that a methane release might have.

Reluctant solutions

The

field of implementing technical climate fixes, or geo-engineering, is full of

controversy, and even those involved in researching the issue see it as a

last-ditch option, a lot less desirable than constraining greenhouse gas

emissions.

"Everybody

working in geo-engineering hopes it won't be needed - but we fear it will

be," said Prof Salter.

Adding

to the controversy is that some of the techniques proposed could do more harm

than good.

The

idea of putting dust particles into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight,

mimicking the cooling effect of volcanic eruptions, would in fact be disastrous

for the Arctic, said Prof Salter, with models showing it would increase

temperatures at the pole by perhaps 10C.

And

last year, the cloud-whitening idea was also criticised by scientists who

calculated that using the wrong droplet size could lead to warming - though

Prof Salter says this can be eliminated through experimentation.

He

has not so far embarked on a full costing of the land-based towers, but

suggests £200,000 as a ballpark figure.

Depending

on the size and location, Prof Salter said that in the order of 100 towers

would be needed to counteract Arctic warming.

However, no funding is currently on the table for cloud-whitening. A proposal to build a prototype ship for about £20m found no takers, and currently development work is limited to the lab.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top