A new and better bionic hand under development connects directly to the nervous system and could one day return dexterity and sensation to amputees, researchers say.

In recent years, a plethora of bionic hands have emerged for amputees. However, surveys of those using such artificial hands have revealed that up to 50 percent of amputees do not use the prosthesis regularly, due to poor functionality, appearance and controllability.

A new and better bionic hand under development connects directly to the nervous system and could one day return dexterity and sensation to amputees, researchers say.

A new and better bionic hand under development connects directly to the nervous system and could one day return dexterity and sensation to amputees, researchers say.

In recent years, a plethora of bionic hands have emerged for amputees. However, surveys of those using such artificial hands have revealed that up to 50 percent of amputees do not use the prosthesis regularly, due to poor functionality, appearance and controllability.

So, to improve the amount of dexterity and sensation of these bionic hands, scientists reasoned they could use interfaces that link the hands with the nervous system, potentially enabling intuitive control and realistic sensory feedback.

"Our dream is to have Luke Skywalker getting back his hand with normal function," researcher Silvestro Micera told TechNewsDaily, referencing the hero in "Star Wars" who gets an artificial hand after his real one is cut off.

[Brainpower: Human Minds May Soon Control Prosthetic Limbs]

Micera is the head of the translational neural engineering lab at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Switzerland, which is one of the collaborators helping to develop the new bionic hand.

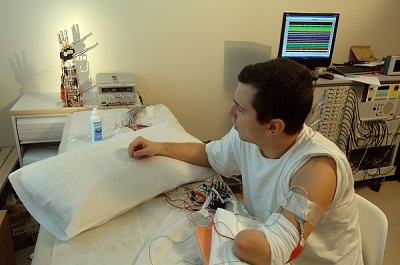

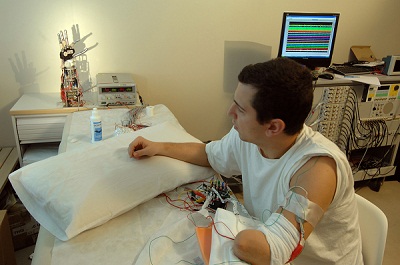

In a four-week clinical trial, Micera and his colleagues found they could improve the sensory feedback an amputee received from bionics by using electrodes implanted into the median and ulnar nerves in the arm near the stump. This helped deliver feelings of touch.

In addition, the researchers analyzed motor neural activity from the nerves, signals used to help control muscles. They found they could tease out signals related to grasping to help control a prosthetic hand placed near the amputee but not physically attached to the person's arm. In other words, it may be possible to develop an artificial hand that can transmit signals to and respond to data from the brain.

"We could be on the cusp of providing new and more effective clinical solutions to amputees in the next years," Micera said.

Micera and his colleagues also announced a new clinical trial that will soon connect the prosthetic hand directly to a patient as part of the Italian Ministry of Health's NEMESIS project. They hope to further improve sensory feedback and overall control of bionics this way.

A key problem is how electricity from the electrodes can inflame cells, forcing the body to grow tissue around the electrodes that dampen signals to and from the bionic hand. Micera suggested drugs or coatings on the electrodes might help prevent such inflammation.

Natural hands normally possess 22 degrees of freedom, meaning they can flex 22 different ways — for instance, they can spread fingers apart. While 22 degrees of freedom are currently unrealistic for prosthetic hands, the four or five different grasping tasks the research team's device can provide can be very helpful, Micera said.

In the future, artificial hands may connect not only with nerves in the periphery of the nervous system, such as those in the limbs, but may also link with the spinal cord. "A hybrid solution that combines both approaches may be the way to go," Micera said.

Future research might also have amputees prepare for what bionic hands might feel like using virtual-reality experiments that could help them reconstruct their body images. "In the medium term, we'd like to have virtual-reality environments for training patients," Micera said.

Still, much work remains before artificial hands are as capable as natural ones.

"I think the Luke Skywalker hand is probably 20 or 30 years away, maybe even more," Micera said.

The scientists recently detailed their findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top