The new technology is a novel catalyst that performs almost as well as cost-prohibitive platinum for so-called electrolysis reactions, which use electric currents to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. The Rutgers technology is also far more efficient than less-expensive catalysts investigated to-date.

The new technology is a novel catalyst that performs almost as well as cost-prohibitive platinum for so-called electrolysis reactions, which use electric currents to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. The Rutgers technology is also far more efficient than less-expensive catalysts investigated to-date.

"Hydrogen has long been expected to play a vital role in our future energy landscapes by mitigating, if not completely eliminating, our reliance on fossil fuels," said Tewodros (Teddy) Asefa, associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology in the School of Arts and Sciences. "We have developed a sustainable chemical catalyst that, we hope with the right industry partner, can bring this vision to life."

Asefa is also an associate professor of chemical and biochemical engineering in the School of Engineering.

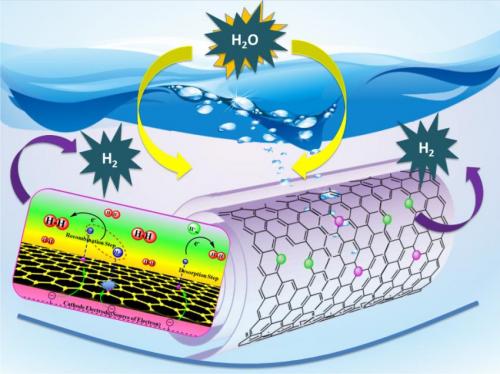

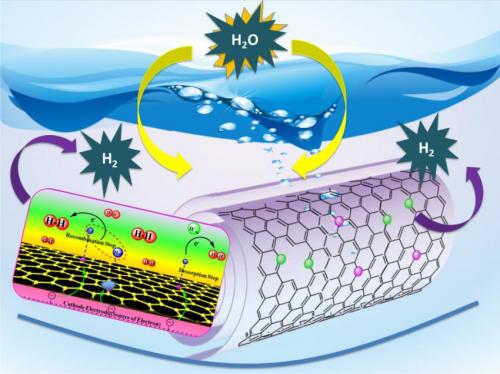

He and his colleagues based their new catalyst on carbon nanotubes – one-atom-thick sheets of carbon rolled into tubes 10,000 times thinner than a human hair.

Finding ways to make electrolysis reactions commercially viable is important because processes that make hydrogen today start with methane – itself a fossil fuel. The need to consume fossil fuel therefore negates current claims that hydrogen is a "green" fuel.

Electrolysis, however, could produce hydrogen using electricity generated by renewable sources, such as solar, wind and hydro energy, or by carbon-neutral sources, such as nuclear energy. And even if fossil fuels were used for electrolysis, the higher efficiency and better emissions controls of large power plants could give hydrogen fuel cells an advantage over less efficient and more polluting gasoline and diesel engines in millions of vehicles and other applications.

In a recent scientific paper published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition, Asefa and his colleagues reported that their technology, called "noble metal-free nitrogen-rich carbon nanotubes," efficiently catalyze the hydrogen evolution reaction with activities close to that of platinum. They also function well in acidic, neutral or basic conditions, allowing them to be coupled with the best available oxygen-evolving catalysts that also play crucial roles in the water-splitting reaction.

The researchers have filed for a patent on the catalyst, which is available for licensing or research collaborations through the Rutgers Office of Technology Commercialization. The National Science Foundation funded the research.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top