All over the world, scientists are creating microscopic "nanobots" for purposes such as delivering medication to precisely-targeted areas inside the body. In order for those tiny payload-carrying robots to get to their destination, however, they need some form of propulsion. Although some systems are already in development, a team of Israeli and German scientists may have come up with the most intriguing one yet, in the form of what they claim is the world's smallest propeller.

All over the world, scientists are creating microscopic "nanobots" for purposes such as delivering medication to precisely-targeted areas inside the body. In order for those tiny payload-carrying robots to get to their destination, however, they need some form of propulsion. Although some systems are already in development, a team of Israeli and German scientists may have come up with the most intriguing one yet, in the form of what they claim is the world's smallest propeller.

All over the world, scientists are creating microscopic "nanobots" for purposes such as delivering medication to precisely-targeted areas inside the body. In order for those tiny payload-carrying robots to get to their destination, however, they need some form of propulsion. Although some systems are already in development, a team of Israeli and German scientists may have come up with the most intriguing one yet, in the form of what they claim is the world's smallest propeller.

The cockscrew-shaped prop was created by researchers from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, and the Institute for Physical Chemistry at the University of Stuttgart.

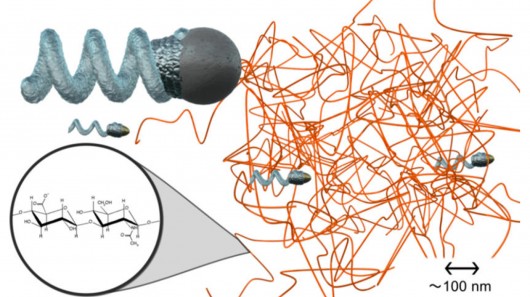

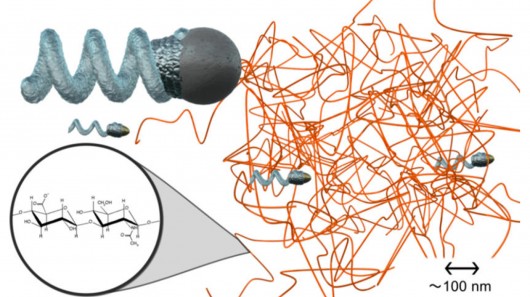

It's actually a curled filament made of silica and nickel, measuring just 70 nanometers wide by 400 nm long – according to the team, that's 100 times smaller than the diameter of a human blood cell.

Instead of carrying its own motor, the propeller is powered by an externally-applied weak rotating magnetic field. This causes the prop to spin, driving it and its attached payload forward.

In order to test it, the scientist placed it in a hyaluronan gel, which is similar in consistency to bodily fluids. Like those fluids, the gel contains a mesh of entangled long polymer protein chains. In previous studies, larger micrometer-sized propellers got caught in these chains, slowing or completely halting their progress. The new nanoprop, however, was able to move relatively quickly by simply passing through the gaps in the mesh.

"One can now think about targeted applications, for instance in the eye where they may be moved to a precise location at the retina," said team member Peer Fischer, of the Max Planck Institute.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top