Physicists have unveiled a raft of new findings about neutrinos bombarding the Earth from above, below - and within.

An experiment built in a vast slab of Antarctic ice has doubled its count of "cosmic neutrinos" from outer space, by searching for arrivals passing through the planet from the north.

Physicists have unveiled a raft of new findings about neutrinos bombarding the Earth from above, below - and within.

An experiment built in a vast slab of Antarctic ice has doubled its count of "cosmic neutrinos" from outer space, by searching for arrivals passing through the planet from the north.

The same team this week announced the highest-energy neutrino ever detected.

Meanwhile, a detector in Italy reported the first firm evidence for neutrinos produced beneath the Earth's crust.

These "geo-neutrinos" carry much less energy but can inform scientists about the radioactive processes generating heat deep within our planet.

The fast-moving neutrinos from space, by contrast, offer clues about mysterious, violent sources of radiation beyond our own galaxy.

Neutrinos are subatomic particles with no charge and almost no mass, which very rarely interact with anything. This means they can practically cross the Universe in a straight line, passing through entire planets undeflected - and undetected.

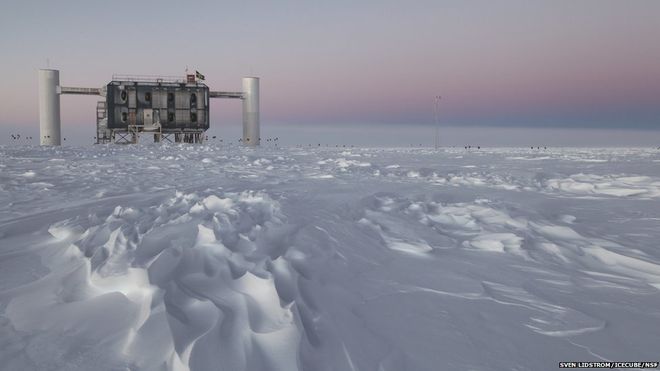

But the IceCube collaboration has laced a cubic kilometre of ice beneath the South Pole with light sensors, to record the flashes created when a neutrino very occasionally bumps into an atom.

Pole to pole

In 2013 IceCube announced the first ever detectionof neutrinos from outside the Solar System: 28 of the particles were caught moving at energies far beyond the reach of humanity's best particle accelerators. Since then, the count of such "cosmic neutrinos" has climbed above 50.

This week at a conference in the Netherlands, the team announced a record-breaking event that their icy instrument witnessed in June 2014.

They have evidence for a neutrino arriving with at least 2,600 trillion electronvolts (teraelectronvolts, TeV) of energy - hundreds of times more than protons inside the Large Hadron Collider, even after its historic revamp. IceCube's previous record was 2,000 TeV.

That makes this neutrino the most energetic space particle ever detected. It is also the fastest, but only by a whisker: all neutrinos travel perilously close (but not above) the speed of light, and a tiny speed increase requires a huge energy boost.

What is more, that energy value is only a minimum. The neutrino itself never made it into the detector; what IceCube glimpsed was a different particle called a muon - the product of a "muon neutrino" (one of three different flavours) arriving from the north.

"It was made by a neutrino that came through the Earth somewhere below our detector," said IceCube's principal investigator Francis Halzen, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

By doing what Prof Halzen calls "back of an envelope" physics calculations, his team can reconstruct the neutrino interaction that spat the muon into the ice, where it dumped those 2,600 TeV.

For a slippery, near-massless particle, this neutrino packed a punch.

"Using standard model physics, the energy of this neutrino is somewhere around 5,000-10,000 TeV, with the most likely value somewhere in the middle," Prof Halzen explained.

"This neutrino packs about 1,000 times the energy of the LHC beam. It is spectacular."

In fact, this type of evidence is what IceCube physicists have used to double their overall count of cosmic neutrinos. They have been busy re-analysing the same two-year tranche of data that has already yielded more than 50 such galactic interlopers, all of which were electron or tau neutrinos (the other two flavours) arriving directly from the southern sky.

In a paper to be published soon in Physical Review Letters, the team turns its attention to the north - revealing a similar number of muon neutrinos which flew into the planet in the northern hemisphere. Eventually, each one bumped into something and blasted a muon into the ice, just like the June 2014 record-breaker.

"This new method gives us muon neutrinos of similar numbers, so our count is up well above 100 now," Prof Halzen told the BBC.

Importantly, muons are comparatively heavy - so when the sensors in the ice glimpse them rumbling past, their trajectory can be reconstructed. That turns IceCube into a telescope, peering northwards through the planet to see neutrinos arriving from the Universe's most ferocious, far-flung corners.

"We can reconstruct the muon track to better than half a degree," Prof Halzen said. "This is totally going to change the astronomy we can do."

Bombardment from within

Neutrinos are also commonly produced with much lower energy, much closer to home.

Rather than a slab of ice, the Borexino experiment buried under Gran Sasso in Italy contains 200 tonnes of specialised oil, filling an immense, spherical vat that is similarly studded with light sensors.

Borexino was built to catch low-energy neutrinos spat out by the nuclear reaction at the heart of the Sun. And it was successful - but the international team has now used seven years' worth of data to look inside the Earth itself.

The Borexino experiment's stainless steel sphere is studded with light sensors

Our planet's interior generates vast amounts of heat: about 20 times the combined output of all the world's power stations. Much of it is radioactive heat - but scientists don't know exactly how much.

"The only way to really understand how much heat comes from radioactivity is to measure the neutrinos coming from inside," explained Aldo Ianni, a member of the Borexino collaboration.

Detectors like Borexino or KamLAND in Japan have glimpsed such "geo-neutrinos" already, along with countless stray neutrinos produced by nuclear power stations right across the globe.

But in a paper due for publication in Physical Review D, the Borexino team presents ground-breaking evidence for neutrinos coming from beneath the Earth's crust, in the layer called the mantle.

The huge data set contained 77 candidate neutrinos, of which Dr Ianni said some 24 were calculated to come from the Earth and not from nuclear reactors.

And within those 24, the team is almost - but not completely - certain that some arrived from the mantle. This is because there is uncertainty attached to each stage of the calculation.

"It's at 98%, the confidence level - which means there is still a small probability that there is no signal from the mantle," Dr Ianni said. That small probability is too large for an official "discovery" according to the usual rules of particle physics.

"It's small, but in terms of physics it should be much smaller."

Borexino's detector is filled with a specially made hydrocarbon

fluid

Dr Jeanne Wilson is a particle physicist at Queen Mary University of London who works on the T2K neutrino experiment in Japan. She agreed that the Borexino findings were preliminary but important.

"From previous results, we could say with good confidence that we were seeing geo-neutrinos - but the more you detect, the more information you can extract on where they're coming from.

"We're getting to the point now where you can start to do these analyses."

"I don't think there's anything in these models that contests the models we currently have for the Earth - but they're proving that we're getting to the point where neutrinos will actually help."

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top