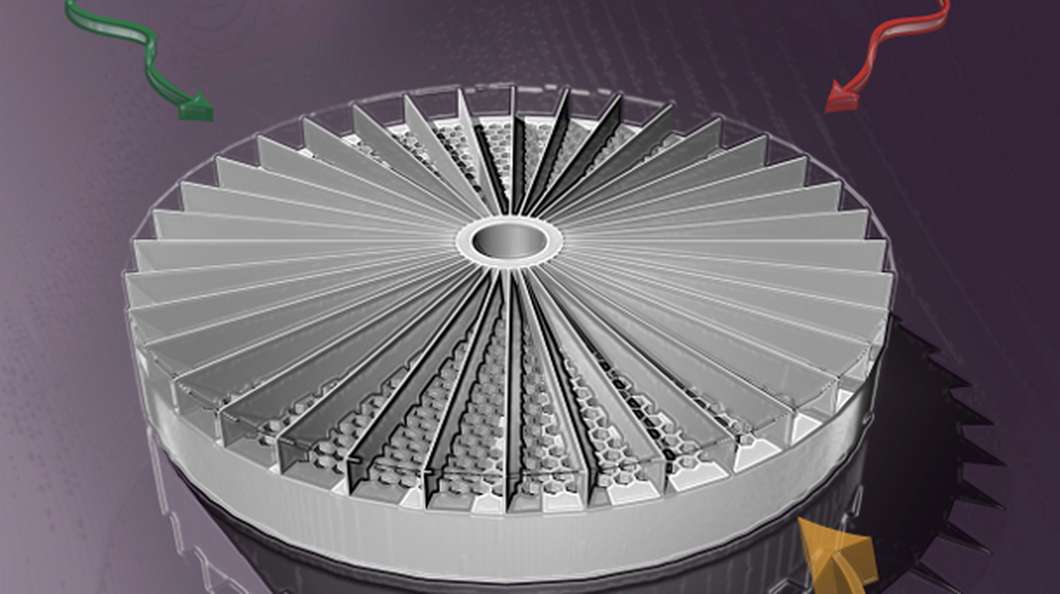

To create the sensor, scientists at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina used a class of materials known as metamaterials, which boast properties not found in nature, and a signal processing technique known as compressive sensing. The disk-shaped device is made of plastic and doesn't have any electronic or moving parts. Rather, it features a honeycomb-like structure and is split into dozens of slices which each feature a unique pattern of cavities of different depths. It is these cavities that distort the sound waves and give the sensor its unique capabilities.

"The cavities behave like soda bottles when you blow across their tops," says Steve Cummer, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke. "The amount of soda left in the bottle, or the depth of the cavities in our case, affects the pitch of the sound they make, and this changes the incoming sound in a subtle but detectable way."

The sound distortions have specific signatures that relate to the honeycombed slice it passed over. When the resulting sounds are picked up by a microphone and processed by a computer, the unique distortions make it possible to separate noises from one other, even if they were all jumbled together. The sensor, the researchers claim, can even separate simultaneous sounds that originate from different directions, thanks to the way each sound is distorted.

In tests, three identical sounds were sent from three different directions to the sensor prototype. Results showed that it was able to distinguish between these noises with an accuracy of 96.7 percent. The team hopes to scale the 6 in (15 cm) -wide prototype down to a smaller size to allow it to be integrated into various devices. Aside from applications in consumer electronics, its creators say it could also find uses in other areas.

"I think it could be combined with any medical imaging device that uses waves, such as ultrasound, to not only improve current sensing methods, but to create entirely new ones," says Abel Xie, the study’s lead author. "With the extra information, it should also be possible to improve the sound fidelity and increase functionalities for applications like hearing aids and cochlear implants. One obvious challenge is to make the system physically small. It is challenging, but not impossible, and we are working toward that goal."

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top