Nanoparticles as a vehicle for delivering drugs precisely where they are needed promise to be a major revolution in medical science. Unfortunately, retrieving those particles from the body for detailed study is a long and involved process. But that may soon change with a team of engineers at the University of California, San Diego developing a technique that uses an oscillating electric field to separate nanoparticles from blood plasma in a way that may one day make it a routine procedure.

At a scale hundreds of times smaller than the width of a human hair, nanoparticles are so small and of such low density that separating them from blood plasma currently relies on some fairly brute force methods. Usually, this involves adding a chemical tag to the particles or diluting the plasma while adding a high concentration sugar solution, then spinning the mixture in a centrifuge.

The problem is that this is a bit like kneading bread dough one too many times. Too many manipulations can change the nanoparticle's normal behavior and some kinds can even be damaged. The UC San Diego's team's goal was to come up with a simpler separation technique that required fewer steps. In this way, doctors and scientists would have a more efficient way of studying drug-delivery systems and tailoring treatments to suit individual patients.

"We were interested in a fast and easy way to take these nanoparticles out of plasma so we could find out what's going on at their surfaces and redesign them to work more effectively in blood," says Michael Heller, a nanoengineering professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

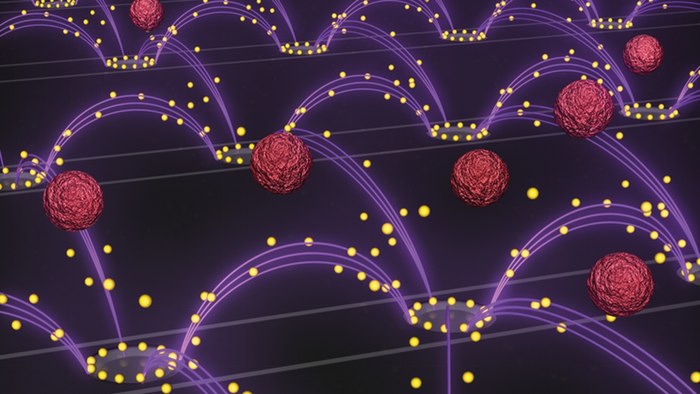

Their answer was a dielectrophoresis collection chip, which is about the size of US dime. Based on technology developed by UC San Diego and built by Biological Dynamics, the new chip is made up of hundreds of tiny electrodes that generate a rapidly oscillating electric field even in the high salt concentrations found in human blood. According to the team, the technique requires no alterations to the plasma or the nanoparticles.

When a drop of plasma is introduced into the chip, the electric field oscillates at 15,000 times per second, which causes the positive and negative charges inside the nanoparticles to reorient themselves, but at a different speed from the plasma particles. Because the charge imbalance attracts the particles to the electrodes, this pulls the nanoparticles to one side in process that takes about seven minutes.

Though the present work has concentrated on medical applications, the team says that the new chip technology could be also find use in environmental and industrial applications.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top