Scientists at Weill Cornell

Medicine have developed a computational technique that greatly increases the

resolution of atomic force microscopy, a specialized type of microscope that

"feels" the atoms at a surface. The method reveals atomic-level

details on proteins and other biological structures under normal physiological

conditions, opening a new window on cell biology, virology and other

microscopic processes.

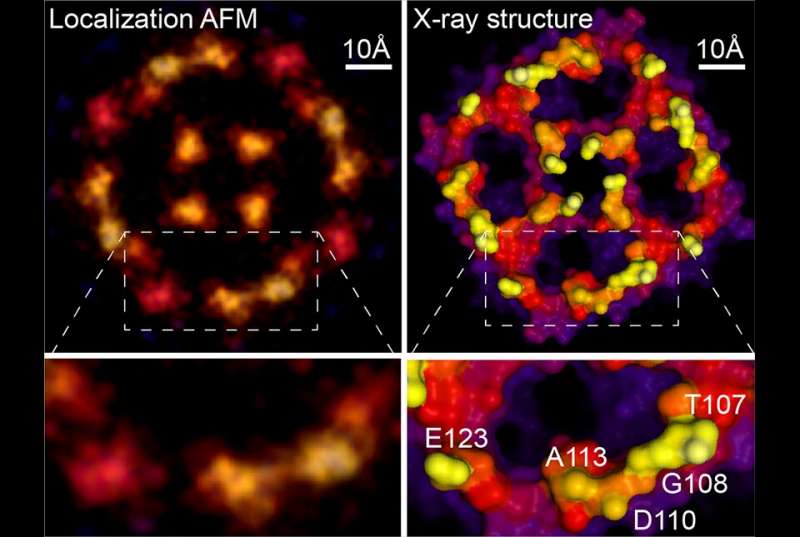

In a study, published June 16 in Nature, the investigators describe the new technique, which is based on a strategy used to improve resolution in light microscopy.

To study proteins and other biomolecules at high resolution, investigators have long relied on two techniques: X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. While both methods can determine molecular structures down to the resolution of individual atoms, they do so on molecules that are either scaffolded into crystals or frozen at ultra-cold temperatures, possibly altering them from their normal physiological shapes. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) can analyze biological molecules under normal physiological conditions, but the resulting images have been blurry and low resolution.

"Atomic force microscopy can easily resolve atoms in physics, on solid surfaces of silicates and on semiconductors, so it means that in principle the machine has the precision to do that," said senior author Dr. Simon Scheuring, professor of physiology and biophysics in anesthesiology at Weill Cornell Medicine. "The technique is a bit like if you were to take a pen and scan over the Rocky Mountains, so that you get a topographic map of the object. In reality, our pen is a needle that is sharp down to a few atoms and the objects are single protein molecules."

However, biological molecules have many small parts that wiggle, blurring their AFM images. To address that problem, Dr. Scheuring and his colleagues adapted a concept from light microscopy called super-resolution microscopy. "Theoretically it wasn't possible by optical microscopy to resolve two fluorescent molecules that were closer together than half the wavelength of the light," he said. However, by stimulating the adjacent molecules to fluoresce at different times, microscopists can analyze the spread of each molecule and pinpoint their locations with high precision.

Instead of stimulating fluorescence, Dr. Scheuring's team noted that the natural fluctuations of biological molecules recorded over the course of AFM scans yield similar spreads of positional data. First author Dr. George Heath, who was a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medicine at the time of the study and is now a faculty member at the University of Leeds, engaged in cycles of experiments and computational simulations to understand the AFM imaging process in greater detail and extract the maximum of information from the atomic interactions between tip and sample.

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top