One of the major issues in

general relativity that separates it from other descriptions of the universe,

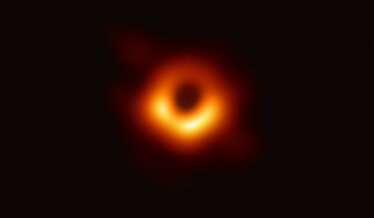

like quantum physics, is the existence of singularities . Singularities are

points that when mathematically described give an infinite value and suggest

areas of the universe where the laws of physics would cease to exist — i.e.

points at the beginning of the universe and at the center of black holes.

A new paper in Nuclear Physics B, published by Roberto Casadio, Alexander Kamenshchik, and Iberê Kuntz from the Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università di Bologna, Italy, suggests that extending the treatment of singularities in classical physics into quantum physics could help to solve this disparity between branches of physics.

"No description of nature is perfect and complete. Every theory has its domain of applicability, beyond which it breaks down and its predictions no longer make sense," Casadio says. As an example, he cites Newton's theories, which are still robust enough to send rockets to space, but fall down when describing the very small, or the tremendously massive.

"This is a serious issue because general relativity — the theory that best describes the gravitational interaction at present — predicts the existence of singularities quite generically," Casadio says. "It is like having a hole in space, where nothing can exist, but into which observers and everything else will fall nonetheless."

Casadio suggests that this can be envisaged as a piece of paper with a small hole in it. "You can move the tip of your pen on the paper, which represents the movement of a particle, but if you reach the hole your pen suddenly stops drawing and the particles suddenly disappear," he says. "This illustrates how singularities are theoretical obstacles preventing us from fully understanding nature."

Casadio adds that the fact that physics ceases to exist at singularities leads to unanswered questions such as: What really happened at the beginning of the universe? Was everything born out of a point that never really existed? What happens to a particle when it falls into the center of a black hole?

"These open questions are the very reason we are compelled by our curiosity to pursue this line of investigation," he says. "Our approach heavily relies on the methods of Quantum field theory (QFT): the framework that combines quantum mechanics and special relativity and gives rise to the very successful standard model of particle physics."

The authors used the tools of QFT to construct a mathematical object that can signal the presence of singularities in experimentally measurable quantities. This object, which they have named the "functional winding number" is non-zero in the presence of singularities and vanishes in their absence.

This approach has revealed that certain singularities predicted theoretically do not affect quantities that can in principle be measured experimentally, and therefore remain harmless mathematical constructs.

"If our formalism survived scientific scrutiny and turned out to be the correct approach, it would suggest the existence of a very deep physical principle, so the choices of physical variables are rather unimportant," Casadio concludes. "This could be consequential for our understanding of physics, even beyond the subject of singularities."

Previous page

Previous page Back to top

Back to top